Around my last birthday, I figured I was finally old enough to attempt building something entirely with hand tools but I knew the project was doomed–my standard of taste far exceeds my standard of craft– so I made a deal with myself: Build a something that looked good at three feet. Any closer and I would be bound to see the flaws but if I could tolerate it a yard away, I could count the project a success.

Around my last birthday, I figured I was finally old enough to attempt building something entirely with hand tools but I knew the project was doomed–my standard of taste far exceeds my standard of craft– so I made a deal with myself: Build a something that looked good at three feet. Any closer and I would be bound to see the flaws but if I could tolerate it a yard away, I could count the project a success.

I chose a jointed box, something small enough I could tuck under the bed. Note especially that I didn’t NEED a box. This is not a practical project. I would have likely slapped one together with nails and butted joints if I actually had a use for one. This project was one of those endeavors where the process is as important as the final product. I just had to remind myself that, given my zealous beginner-level skills, what I came up with wouldn’t be very “Zen” to meditate upon at up close.

For wood, I used the cut-off cedar scraps from our barn. I selected pieces that, more or less, were knot-free. The planking was rough cut on one side and since I didn’t want a box of splinters, I hauled out one the handplanes I inherited from my father. I have one wooden hand plane from my grandfather that’s stamped with his name. I’ve tuned them up as best I could using resources I’ve found in books and on-line but I’ve never had an occasion to learn their use. As I dragged that old, dime-store quality tool across the board, chattering along until I adjusted the throat, I hoped my ancestors weren’t watching me too closely. I don’t have a proper bench for wood work, that is, it lacks dogs and hold fasts, so I clamped the board as best I could. It wasn’t ideal, but I wasn’t going for ideal.

I “designed” the box around the wood I had, guided by my sense of proportion to end up with one 6″ deep, 8″ wide and 16″ long. It’s a compact size, easy to hold. The lid is a single board with hand cut and chiseled rabbets that allow it to seat into the box. The sole bit of fanciness is a 45 degree flare at the ends of the lid which allows the box to be unlidded easily without a pull. I have worked hard at learning to hand saw, the graceful flow of arm and wrist, the surrender of intention to the teeth of the blade. I take great encouragement from Chris Schwartz’ maxim “If you can see the line you can cut the line with a handsaw” … and yet, even at this early stage, my work started to go just a bit wrong. Not horribly, mind you, but enough that I needed to remind myself of my modest victory conditions.

I “designed” the box around the wood I had, guided by my sense of proportion to end up with one 6″ deep, 8″ wide and 16″ long. It’s a compact size, easy to hold. The lid is a single board with hand cut and chiseled rabbets that allow it to seat into the box. The sole bit of fanciness is a 45 degree flare at the ends of the lid which allows the box to be unlidded easily without a pull. I have worked hard at learning to hand saw, the graceful flow of arm and wrist, the surrender of intention to the teeth of the blade. I take great encouragement from Chris Schwartz’ maxim “If you can see the line you can cut the line with a handsaw” … and yet, even at this early stage, my work started to go just a bit wrong. Not horribly, mind you, but enough that I needed to remind myself of my modest victory conditions.

Again, lacking a proper wood working bench, I clamped the pin boards in my metal vice, once I’d padded the jaws. I marked and cut both boards at the same time, using cool tools from Lee Valley (their marking gauge and flush cutting dozuki saw.) I did my best, I swear, to transfer those marks to the other boards but again there was “slippage.” I cheated, I suppose, and cut the waste on the outer fingers but used a hand sharpened chisel to pare away the waste in the other boards. Again, it sure would have been easier with a proper work bench.

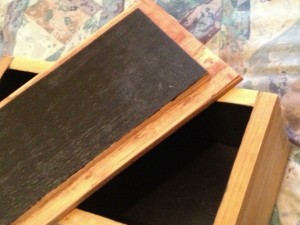

My one flat out mistake was to think that the bottom board would just magically fit. It does, more or less, but there is enough of a gap around one of the edges that a bit of black paint seeped out during finishing. Again it’s on the bottom and likely someplace I won’t notice at three feet away but if I make a similar box in future, I might fit the bottom to the sides with a rabbet. Dry fitting the pieces was a bit of an exercise in patience. The errors for the most part were corrected by shaving off a bit from the pins. There’s only one place where a glued in shim is cleverly assisting the joint.

Let me confess: I’m a sucker for doweled joints. There’s just something attractive to my eye about the little dot of end grain in the middle of a pin’s rectangle. I figured my little box could use all the support it could get. Here’s another confession. I believe I used the old-timey egg beater style drill to make the final hole but I used my battery-powered hand drill to make the pilot holes. Next time, I’ll use the electric for all the drilling. I cut off the dowels with the flush-cut dozuki and was a bit amazed as how much dowel the process took.

I trimmed and and futzed and sanded by hand and yes, at times, I wish I could have just smoothed away all the imperfections of my joinery using a massive belt sander. The surface feels good in the dark, smooth enough, even though it’s hardly pretty close up.

The lid required another level of ingenuity. I toyed around with various ideas for a pull, discarding them all. I wanted a box I could slide under my bed so no knobs. I didn’t want to make finger holes because they’d let in dust and I’d seen pulls that were gorgeously hand carved into the very lid itself… but I couldn’t kid myself that my skills could pull off something that graceful, even using the three foot rule. I decided to flare the ends of the lid slightly at a 45 degree angle. The sides of the lid are flush with the box but the lid can easily be removed.

The lid required another level of ingenuity. I toyed around with various ideas for a pull, discarding them all. I wanted a box I could slide under my bed so no knobs. I didn’t want to make finger holes because they’d let in dust and I’d seen pulls that were gorgeously hand carved into the very lid itself… but I couldn’t kid myself that my skills could pull off something that graceful, even using the three foot rule. I decided to flare the ends of the lid slightly at a 45 degree angle. The sides of the lid are flush with the box but the lid can easily be removed.

I ran into trouble making those dreams a reality. My fancy hand miter box wouldn’t accept the 8″ wide board so I improvised using an older chop saw while angling the board, not the blade. Despite my impromptu jig, the cuts worked more or less as intended. I’d never hand cut a rabbet before… but then I’d never hand cut finger joints either. I marked, muttered a prayer and did my best which turned out to be good enough. The chisel pared away the worst of my mistakes, mostly involving a remarkably poorly placed knot and a bit of hand sanding made things look almost sharp.

Finish was a bit of tinted sealer for the outside and a couple coats of flat black on the inside. I’m usually partial to orange shellac but I figured the abuse the box would likely endure might be too much for such a fragile, albeit easily fixed, top coat. I’ll rub in some paste wax at some point.

I am very pleased with my “three foot box.” It sits right beside my bed and is often the last thing I see at night. As Long as I keep it just a little farther away than arm’s reach, it’s a thing of pure delight. I learned a great deal building it, even beyond the skills I honed. I learned to love myself and accept my abilities as they are, even as I’m striving for improvement.

One Response

Stay in touch with the conversation, subscribe to the RSS feed for comments on this post.

Continuing the Discussion